Rental M&A: will there be a Covid discount?

10 February 2021

The pandemic has inevitably reduced mergers and acquisitions activity in the rental sector, but what impact will it have on company valuations? Jeff Eisenberg considers the question.

Over the last 25 years, the equipment rental industry has seen consolidation, particularly in North America and Europe. Acquisition prices were often excitingly high, set on a multiple of EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation).

What has the Covid crisis done to valuations, and why? Do the EBITDA multiples from the 1990s and early 2000s match today’s valuations? What does this mean for buyers, sellers, and debt funders?

Transactions post March 2020

Very few transactions have occurred in rental since March 2020 for several reasons. Those that have been completed have been quiet about the price paid. Unlike in the boom years, we don’t have multiple disclosed rental company acquisition prices to read in the United Rentals and other investor presentations, from which to calculate an average. The uncertainty is the key, which has direct and indirect effects, including the nervous banks which may provide half or more of the acquisition price.

|

The author Jeff Eisenberg has 23 years of experience in the rental industry. Starting at Genie in the 1990s financing rental company expansions, he has advised, started, run, acquired and sold rental companies on multiple continents.  Jeff Eisenberg Jeff Eisenberg

Since 2018 he has been CEO of Hydrainer Holdings, a pump rental business and manufacturer in the UK. He is also an advisor to the board of Energia in Saudi Arabia. Contact +44 7900 916933, or e-mail [email protected] |

The main consolidators of rental companies - a few private equity businesses and companies including United Rentals, Ashtead Group, Loxam, Kiloutou and Boels - seem to have taken a pause.

The publicly traded United Rentals presented that its latest M&A strategy is “disciplined and opportunistic” and it’s easy to imagine all transactions at the top of the market will wait for a successfully administered vaccine or other end to the Covid crisis.

United Rentals always comes up in conversation when discussing rental company acquisitions. Their last investor presentation says they have acquired 275+ rental companies, acquiring literally billions of US$ of rental operations.

Their model has focussed on buying well run companies with strong growth and profitability, even if expensive, rather than looking for bargains or turnarounds.

They consistently tell their shareholders, which are stock market share investors, they realise value in acquisitions in two areas. The first is “grow the core” business, adding profitable volume while saving on overheads, for which they publish quantifiable dollar goals and outcomes. The second is “cross selling” especially when adding speciality rental categories, particularly fluid control, again with measurable goals. “Grow the core” may be a difficult sell if the rental industry is not growing (hopefully temporarily); and “cross selling” in a declining market is also a challenge.

Valuations in good times

How much should a rental company pay for an acquisition? In good times in the late 1990s, when many rental companies were growing at 15% or even more per year, the accepted wisdom of 6 times EBITDA (less company debt) became the starting point for negotiations.

Big acquisitions with big growth, and a unique market position, like Baker Corp, the tank and fluid control rental specialist, could command big multiples. In 2018, United acquired Baker Corp for $720m, which is over 9x the $79m adjusted EBITDA.

Does that mean all rental companies are worth 9x EBITDA?

In established markets like the North America and Europe, banks, bond investors, and other lenders readily provide debt to help acquisition funding. How much of that 6x EBITDA could be funded by debt?

If the banks are feeling bullish and rental asset valuations are steady, then as a rule of thumb 3x, sometimes 4x the EBITDA could be taken as new debt to finance the company acquisition.

This would leave just 2x EBITDA to be financed by equity, although growing companies would expect to have “headroom” and additional cash or finance available to fund growing rental fleets.

Many banks are quietly admitting they are slow to process new loans, and remain focussed on their existing portfolios, many of which are under unprecedented pressure. Some are making more conservative finance proposals post March 2020, and this seems to be worsened by worried asset valuers.

EBITDA of large rental companies?

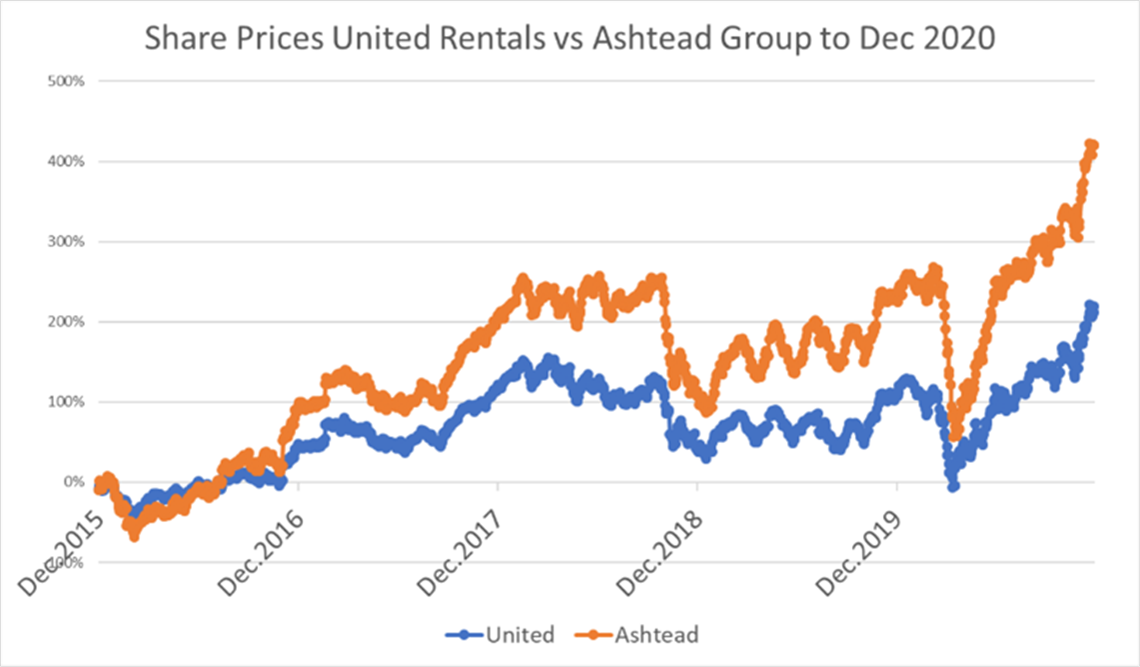

United Rentals’ own EBITDA multiple, calculated by taking its share price plus its debt, is 11.69x EBITDA (as on 4 Dec 2020). Ashtead/Sunbelt trades at 8.83x EBITDA. This seems high during crisis year 2020, considering that the companies both report quarterly numbers.

Profitability for United is down 48.6% for the quarter, Ashtead is down 37.1%. Despite uncertainty (December 2020), the US Dow Jones share index is in record high territory, along with the German DAX. The UK FTSE has recovered most of its March/April 2020 drop.

These high EBITDA multiples seem inconsistent with the idea that high multiples are linked to rental companies that are growing. Is the stock market simply temporarily crazy? Is United Rentals really worth more now than at the end of 2019, pre-Covid, when it was more profitable than today?

One of the biggest challenges of using historical data to value rental companies is that ‘rules of thumb’ are remembered selectively and accepted as firm unchanging truth. A 6 to 7x EBITDA? This was an average from a stream of rental company acquisitions in the late 1990s and up until 2008, with many fewer examples since, especially where detailed numbers are visible.

One often used rule of thumb is that there is a predictable discount in valuation of around 30% for private rental companies compared to stock market traded companies.

The advantage of publicly traded companies is principally that up to a point any number of shares can be sold, almost instantly. Therefore, in a market like rental which has been growing and consolidating for decades, the EBITDA multiple of the acquirer, discounted by 30%, can also be a starting point for negotiations.

Valuation post March 2020

Pricing and valuation models have been discussed during the post March 2020 period. These include: ignoring the two ‘lost quarters’ of April to June and July to September 2020, and replacing these with 2019 numbers, or some other correction. The downturn isn’t necessarily over, though, and seems to be dragging into the final quarter as many countries experience a second wave of Covid.

Another commonly used tactic in 2020 is for private equity investors to make an initial offer based on financials to the end of 2019 as being a ‘normal’ year, a ‘normal’ multiple of EBITDA (4,5,6 anyone?) with some money held back via deferred consideration or earn out.

Deferred or earn out?

Broadly speaking, an earn out payment is contingent on some target being reached or event happening. This is most useful to the buyer, it makes the acquisition cheaper, initially and lowers risk. It can have upside for the seller, if the earn out amount is higher if the set target is exceeded.

Where the outgoing shareholders are key to the business operation, having them leave some ‘skin in the game’ is a common request, while the new management learns the business.

Deferred consideration is a payment made at an agreed date, principally to lower the cash out paid out by the buyer. Usually, the only condition for the payment is that the company is still solvent, although sometimes deferred consideration is guaranteed by a bank or parent company of the acquirer.

In the fine print, the conditions for the deferred consideration or earn out will likely raise or lower the risk for the buyer or seller. Another definition of the difference is cynical: if you lose sleep, it’s an earn out, otherwise it’s deferred consideration.

Other considerations include the reputation of the investor: do they have a history of using earn outs as after-the-fact price negotiations? Or hypothetically, if the transaction was done in December 2019, would the payment have been made at the end of 2020, despite Covid?

Deferred consideration and earn outs are typically 10 to 50% of the value of the acquisition, payment is often one, three or five years, single or multiple payments.

Selling a rental company now, rather than waiting for 2021 or 2022, with deferral or earn out, could have another large advantage – taxation. Governments are spending large amounts on supporting incomes for people with jobs affected by Covid, as well as seeing tax revenues decline, and will certainly be tempted to raise capital gains tax on business sales.

Negotiation and other factors

A lack of competition and lack of multiple offers for rental company acquisitions is also slowing down M&A activity. One head of M&A for a large rental company consolidator admitted, off the record, that they do want to start discussions with new target companies, but they must be realistic concerning timing.

This might be interpreted cynically as ‘the banks won’t let us do anything today, but we want to be ready when they take off the handcuffs in 2021’. Competition by potential acquirers for rental companies is extremely important. The unstated part of negotiations to buy companies nearly always implies ‘if you don’t pay me 6x EBITDA instead of 5x EBITDA, then I will sell to your competitor’.

In conclusion, this crisis is unique in the history of modern rental because it may end quickly as vaccines and better testing come onstream.

Despite record high share prices for United and Ashtead, it is difficult to see a consistent measurable Covid discount or pattern of deferred consideration or earn outs. The rental company consolidators, private equity investors, banks and the potential sellers of companies would rather wait a few more months.

This article appears in the January-February issue of International Rental News (IRN).

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM